The FDA thought this sham of a report was good enough. If something terrible happened to a woman more than a year after implantation, it wasn’t included.

If something terrible happened to a woman but the investigator didn’t think or didn’t want to say it was “possibly” related to the Essure-such as autoimmune disorders and inflammatory reactions to the toxic metals in Essure-then it wasn’t included.

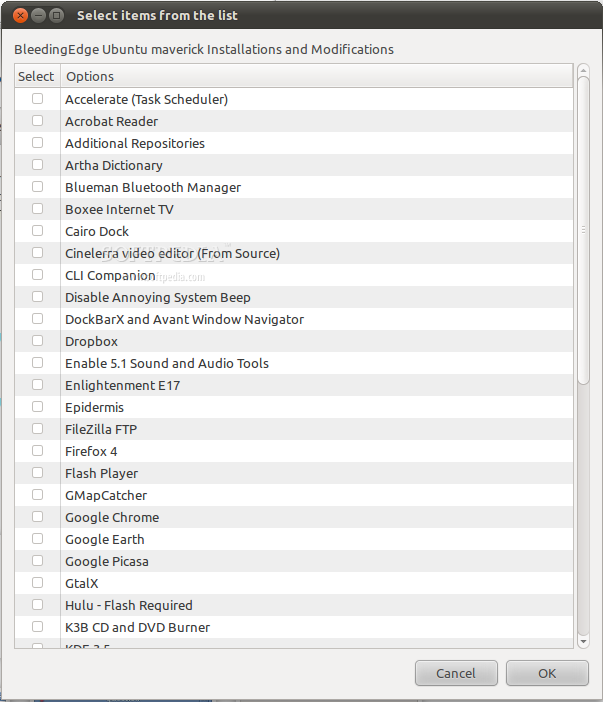

THE BLEEDING EDGE QUESTIONS TRIAL

Look carefully at page 8 of that summary of Essure safety data: that table of “adverse events” only includes those events the clinical trial investigator (who was paid by the manufacturer) said were “possibly” related to the Essure and only those events that occurred in the first year after the implantation. Yet, even the data taken at face value isn’t much: Essure was approved and sold to the public after a single “Phase II” clinical trial (a trial designed mostly to look at whether the implant can function, rather than if it is safe) of 227 women and a single “Phase III” clinical trial of 518 women. As The Bleeding Edge points out through interviews of clinical trial participants, this data was inaccurate, and the researchers routinely changed the participants’ answers to make the device look safer than it was. But the FDA doesn’t see things that way, and so routinely allows inherently risky devices to glide through the 510(k) loophole without any studies.Įssure went through this “PMA” process, which, as we’ll discuss in a minute, is often referred to as “rigorous.” You can read the “safety and effectiveness data” used to approve it. As the FDA says, “Class III devices are those that support or sustain human life, are of substantial importance in preventing impairment of human health, or which present a potential, unreasonable risk of illness or injury.” We can already see one obvious problem: there’s no doubt a complete hip replacement (like the DePuy ASR) or the surgical implantation of a foreign object (like transvaginal mesh) “present a potential, unreasonable risk of illness or injury,” and so should have to go through the premarket approval process. If a medical manufacturer doesn’t want to or can’t use the 510(k) loophole, then they go through the “premarket approval” (“PMA”) process for “Class III” medical devices. The DePuy ASR hip implant used never-before-tested components, and transvaginal mesh was used for a never-before-tested purpose-yet both sailed through the 510(k) loophole. The FDA’s interpretation of “substantial similarity,” however, has gone so far off the rails that the FDA regularly approves medical implants with different designs, different materials, and different purposes. Most medical devices need not undergo any testing because they are approved under a provision that only requires the manufacturer to show “substantial similarity” to some other approved medical device. The Broken Regulation Of Medical DevicesĪs The Bleeding Edge points out, one key problem is the 510(k) loophole, which I’ve written about many times before, and which the Institutes of Medicine long ago recommended be abolished.

Essure was just one part of a broken regulatory system and a corrupted market, and medical device companies often lobbying Congress to make it even worse. If no one ever watched The Bleeding Edge, the film would still be a remarkable success: soon after it premiered, Bayer announced it will discontinue sales of Essure.īut everyone should watch it. I know these awful products well most of my law practice is representing victims of medical devices and pharmaceuticals. The Bleeding Edge, a documentary just released on Netflix, details the many problems with medical devices today, with an emphasis on the suffering of thousands of people due to Bayer’s Essure contraceptive, DePuy’s ASR hip implant, Johnson & Johnson’s transvaginal mesh, and the Da Vinci surgical robot. The medical devices which are tested can pass with a minimal showing, and Congress passed a special law that says that this minimal showing is enough to shut the courthouse doors on victims. Most medical devices aren’t tested with clinical trials.

Yet, those examples above describe the state of the $156 billion American medical device market. What about a car that had just one crash test, at low speed, and Congress had passed a special law making it impossible for anyone to sue the car company, so the company couldn’t be held responsible for people’s injuries? Would you put your family in one?

Imagine if lights, kitchen equipment, and home electronics didn’t need to be tested for electrical shock and fire hazards, and that no one ever certified that the devices were safe.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)